|

B-17 Fortress - s/n 42-3172 (?) RD*? Triangle-H "Chennault's Pappy III" |

|

|

B-17 Fortress - s/n 42-3172 (?) RD*? Triangle-H "Chennault's Pappy III" |

|

| Fiche France-Crashes 39-45 créée le 04-11-2024 | |||||

| Date | Nation |

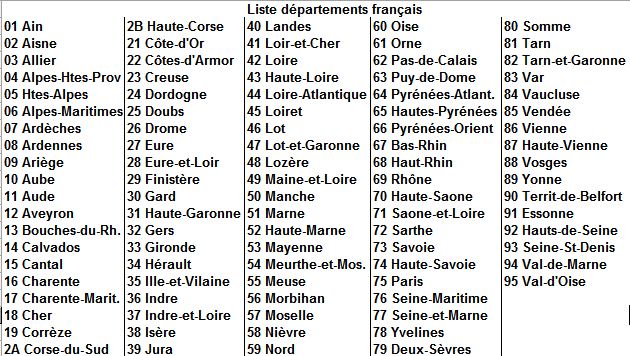

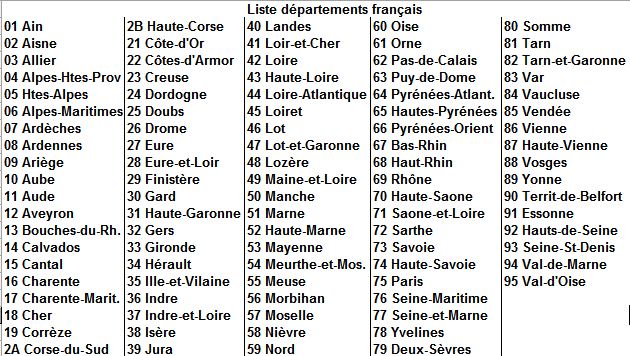

Département Département |

Unité | - | Mission |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26-06-1943 | Etats-Unis | HORS CADRE | 306thBG/423rdBS/8thAF | Tricqueville | |

| Localisation | Retour base de Thurleigh |

|---|---|

| Circonstances | Attaqué par chasseurs, tuant le pilot et blessant gravement le CoP - L'avion est ramené par le 2Lt Cassedy |

| Commentaires | Décollage de la base 111 de Thurleigh, Bedfordshire UK - Equipage resté dans l'avion: Capt Raymond J Check, Pil, tué dans l'avion par obus - Lt/Col James W Wilson, station air executive officer, CoP, sévèrement blessé et brûlé - Major George L Peck, médecin - 1Lt Milton P Balnchett, Nav - 2Lt William P Cassedy, CoP, occupait le poste de Mit Lateral - S/Sgt James A Bobbett, méc, blessé - T/Sgt William J Johnson, Rad - S/Sgt Milton B Edwards, MitA - S/Sgt Terry O Hooks, Mit/L - Sgt Archie H Garrett, MitV - |

| Sources ** | S Lanham (sources: (www.americanairmuseum.com / 306bg.us) |

| Historique | 04/11/2024=Création |

| Grade | Prenom | Nom | Poste | Corps | Etat |

Lieu d'Inhumation Lieu d'Inhumation |

Commentaires |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1Lt | Lionel E Jr | Drew | Bomb | USAAF | Echappé | Rapport #288 inexistant |

| Fiche tech | Correspondance grades | Abréviations utilisées | Filières d'évasion | Camps de Pow | Bases RAF/USAAF | Utilitaires |

|---|

|

Extrait d’Historique: - ( June 27, 1943 Sunday it is. More like Sunday in some ways than most. In the first place, I find my hat is somewhat too small this morning. It is the same with many of us and so there is an aura of relaxation in these parts. There was, of course, an officer’s party. There always is plenty to drink at such affairs. But this time one of my best friends who was to finish his tour of duty yesterday was hit in the neck with an exploding cannon shot that had his head blown completely off. All very horrible. I had a couple of extra drinks. Today is another day and life goes on. And the war goes on too. Note: Because the June 26 mission disaster fell upon two close friends, Ray Check and the 423rd’s original C.O., James Wilson, Fred’s break from his tradition of leaving mission casualty details out of his letters is understandable. A description of what unfolded in Check’s plane, recounted in Gerald Astor’s “The Mighty Eighth” is worth quoting atlength as Fred’s own Combat Diary version is dutifully buttoned up. Astor also provides context, noting that RAF and US Air Force strategy officially changed on June 10. The new goal—a reversal from the position that bombing could be precise enough to justify a high casualty rate—was now to go directly after the German fighter forces and the industries upon which they depend. The new operation was christened “Pointblank.” From Astor, “…the 306th Bomb Group headed for Tricqueville, a German air base in France. It was only a short hop across the Channel and James Wilson, although now serving as the group’s executive officer, arranged to fly with his old squadron in honor of Capt. Raymond Check, an original pilot under Wilson, for whom this would be his twenty-fifth and final mission. Wilson took the left hand command seat while Check acted as co-pilot. The ship’s regular co-pilot, Lt. William Cassedy, decided he could profit from a milk run and flew as one of the waist gunners. Original) - (PARTIE I - Source: 306 Bomb Group – Capt Fred C Baldwin) - Traduction DC via Google): 27 juin 1943. C'est dimanche. Plus que la plupart des autres, à certains égards. Tout d'abord, je trouve que mon chapeau est un peu trop petit ce matin. C'estle cas pour beaucoup d'entre nous et il y a donc une aura de détente dans ces régions. Il y avait, bien sûr, une fête d'officier. Il y a toujours beaucoup à boire dans de telles soirées. Mais cette fois, l'un de mes meilleurs amis qui devait terminer son service hier a été touché au cou par un coup de canon qui a explosé et lui a complètement arraché la tête. Tout cela a été très horrible. J'ai bu quelques verres de plus. Aujourd'hui est un autre jour et la vie continue. Et la guerre continue aussi. Remarque : Étant donné que le désastre de la mission du 26 juin est tombé sur deux amis proches, Ray Check et le commandant original du 423e, James Wilson, la rupture de Fred avec sa tradition de ne pas mentionner les détails des victimes de la mission dans ses lettres est compréhensible. Une description de ce qui s’est passé dans l’avion de Check, racontée dans « The Mighty Eighth » de Gerald Astor, mérite d’être citée longuement, car la version du Combat Diary de Fred est consciencieusement boutonnée. Astor fournit également un contexte, notant que la stratégie de la RAF et de l’US Air Force a officiellement changé le 10 juin. Le nouvel objectif – un renversement de la position selon laquelle les bombardements pouvaient être suffisamment précis pour justifier un taux de pertes élevé – était désormais de s’attaquer directement aux forces de chasse allemandes et aux industries dont elles dépendent. La nouvelle opération a été baptisée « Pointblank ». D’après Astor, « … le 306th Bomb Group s’est dirigé vers Tricqueville, une base aérienne allemande en France. Ce n’était qu’un court saut de puce à travers la Manche et James Wilson, bien que servant désormais comme officier exécutif du groupe, s’est arrangé pour voler avec son ancien escadron en l’honneur du capitaine Raymond Check, un pilote original sous Wilson, pour qui ce serait sa vingt-cinquième et dernière mission. Wilson prit le siège de commandement gauche tandis que Check faisait office de copilote. Le copilote habituel du navire, le lieutenant William Cassedy, décida qu’il pouvait profiter d’un petit tour de contrôle et vola comme l’un des mitrailleurs de bord. Extrait d’Historique: - ( The nineteen effectives from the 306th began to unload on the airdrome. Suddenly, a German fighter attacked Wilson and Check’s ship from out of the sun. The Americans never saw the enemy, whose shells smashed into the cockpit during the bomb run. The explosion of shrapnel killed Check instantly and seriously wounded Wilson. A flash fire enveloped the cock-pit…. Wilson rang the alarm bell, and the bombardier bailed out before any further signal. The engineer, Sgt. James A. Bobbet, descended from his turret and was injured when he grabbed an extinguisher to put out the blaze. According to Wilson, Bobbet laced him with morphine to dull the pain of his wounds and burns while he continued to pilot the aircraft. A history of the 306th states that Cassedy left his waist-gunner post and extricated the body of Check while Wilson, who had been operating the controls with his elbows because the skin from his hands was hanging in long strands, climbed down to the nose of the plane. There the pilot received emergency medical treatment from a flight surgeon who had gone along for the ride. Patched up for the moment, Wilson went back to his post while Cassedy continued to fly the B-17. With all communications systems out and their flares for signaling distress consumed by the fire, Cassedy headed for the Thurleigh home base where he believed the wounded could get the quickest and best medical attention. To add to the copilot’s distress, he was aware that the dead man was to be married to a nurse the next day, and she would be at the end of the runway with a welcoming party to greet her fiancé as he completed his combat tour. Cassedy set the plane down against the flow of traffic and pulled off the runway away from the crowd. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and Wilson received a Distinguished Service Cross for carrying on despite his ‘excruciating pain.’ Indeed, the West Pointer endured nine months of hospitalization and treatment both in the United Kingdom and the U.S. before he could return to duty.”Original) - (PARTIE II): Les dix-neuf équipages du 306e commencèrent à débarquer sur l’aérodrome. Soudain, un chasseur allemand attaqua l'avion de Wilson et Check depuis le soleil. Les Américains ne virent jamais l’ennemi, dont les obus s’écrasèrent dans le cockpit pendant le bombardement. L’explosion des éclats tua Check instantanément et blessa grièvement Wilson. Un feu éclair enveloppa le cockpit… Wilson sonna la sonnette d’alarme et le bombardier sauta avant tout autre signal. L’ingénieur, le sergent James A. Bobbet, descendit de sa tourelle et fut blessé lorsqu’il saisit un extincteur pour éteindre l’incendie. Selon Wilson, Bobbet lui avait administré de la morphine pour atténuer la douleur de ses blessures et de ses brûlures pendant qu’il continuait à piloter l’avion. L’histoire du 306th indique que Cassedy a quitté son poste de mitrailleur et a extrait le corps de Check pendant que Wilson, qui avait manipulé les commandes avec ses coudes car la peau de ses mains pendait en longs brins, est descendu jusqu’au nez de l’avion. Là, le pilote a reçu des soins médicaux d’urgence d’un médecin de l’air qui l’avait accompagné. Soigné pour le moment, Wilson est retourné à son poste pendant que Cassedy continuait à piloter le B-17. Tous les systèmes de communication étant hors service et leurs fusées de détresse consumées par l’incendie, Cassedy s’est dirigé vers la base de Thurleigh où il pensait que les blessés pourraient recevoir les soins médicaux les plus rapides et les meilleurs. Pour ajouter à la détresse du copilote, il savait que le défunt devait se marier avec une infirmière le lendemain, et qu’elle serait au bout de la piste avec une fête de bienvenue pour accueillir sa fiancée alors qu’il terminait sa tournée de combat. Cassedy a posé l'avion à contre-courant du trafic et s'est arrêté sur la piste, loin de la foule. Il a reçu la Distinguished Flying Cross et Wilson a reçu une Distinguished Service Cross pour avoir continué malgré sa « douleur atroce ». En effet, le West Pointer a dû endurer neuf mois d'hospitalisation et de traitement au Royaume-Uni et aux Etats-Unis avant de pouvoir reprendre son service. » (pp. 132-134) Récit de la fuite du Lt Drew: - ( Lionel Drew was Bombardier on the 26 June 1943 mission to the Tricqueville airfield, France, on board B-17 #42-3172. When he heard the alarm bell sounding, Lionel Drew baled out of the Fortress, which was brought back safely to England, piloted by Ray Check's regular Co-Pilot, William Cassedy, who had taken the Waist gunner position that day. Drew went out via the nose hatch, cutting his hands on it, and went by so close to the ball turret, he could have touched it. He opened his chute at 10,000ft and landed in a hay field neat Pont-L'Evêque, 50km NE of Caen, France. The hay was about 3ft high. He pulled in his chute, wadded it up and stood up. He saw a farmer and a boy working on a haystack a hundred feet away. The French farmer was leaning on his pitchfork looking at him. Drew started to run, over to a hedgerow, where he stuffed in his chute and Mae West. The farmer (Hubert Caillaux) came and spoke to him in German, asking for identification. After Drew showed him his dog tags the farmer started to speak in English. He hid him in a hedgerow and about an hour later the farmer returned to ask if Drew wanted something to eat. He said he was thirsty. The farmer brought him a mixture of coffee and calvados, and Drew stayed put. About 10pm the farmer returned and told Drew to follow him, but not to walk with him. They went to the farmer's dirt-floored, stone house where Drew sat down in the kitchen with the farmer, his wife, son and daughter, and friend Ernest. They had soup, black bread and wine. Drew slept in the barn for about a week, hiding in the fields by day. After 4/5 days, the French underground took him over. He was passed on to Georges Castelaine in Pont-l'Evêque who sheltered him in his inn/restaurant. He stayed with the family of three for a couple of days. There was a high ranking German naval officer in the next room. Parisian Pierre Cornet came on a tandem bicycle one Sunday afternoon, and took him 15 miles away to the farm of Edouard and Clara Lanos, at Ouilly-du-Houley, where he stayed for 5 weeks (in July/August). One Andre was also hiding there and it was him who brought food. Drew and André played checkers to pass the time. Lionel Drew's Escape & Evasion Report E&E 288 is not available at NARA (one empty page…) and the rest of the story and following details come from French Helpers' archives. Pierre and Francine Cornet came to fetch Drew and take him to Paris via Lisieux, a town 10km SW of Ouilly-du-Houley. Three days later, Pierre Cornet took Drew from Paris to Joigny (Yonne) where he was passed on to Pierre Argoud of Aillant-sur-Tholon. Antony Leriche of Joigny had also helped Drew on his way. Original) - (PARTIE I - Source: www.americanairmuseum.com via S Lanham) - Traduction DC via Google): Lionel Drew était bombardier lors de la mission du 26 juin 1943 à l'aérodrome de Tricqueville, en France, à bord du B-17 #42-3172. Quand il entendit la sonnerie d'alarme retentir, Lionel Drew sauta en parachute du B-17, qui fut ramené sain et sauf en Angleterre, piloté par le copilote habituel de Ray Check, William Cassedy, qui avait pris le poste de mitrailleur latéral ce jour-là. Drew sortit par la trappe avant, se coupant les mains dessus, et passa si près de la tourelle ventrale qu'il aurait pu la toucher. Il ouvrit son parachute à 10 000 pieds et atterrit dans un champ de foin près de Pont-L'Evêque, à 50 km au nord-est de Caen, en France. Le foin était d’environ 3 pieds de haut. Il rentra son parachute, le froissa et se leva. Il vit un fermier et un garçon travaillant sur une botte de foin à une centaine de pieds de là. Le fermier français s'appuyait sur sa fourche et le regardait. Drew se mit à courir, vers une haie, où il rangea son parachute et Gilet de sauvetage gonflable (du nom de Mary 'Mae' West au buste généreux) Mae West. Le fermier (Hubert Caillaux) vint et lui parla en allemand, lui demandant une pièce d'identité. Après que Drew lui ait montré ses plaques d'identité, le fermier commença à lui parler en anglais. Il le cacha dans une haie et environ une heure plus tard, le fermier revint pour demander à Drew s'il voulait quelque chose à manger. Il dit qu'il avait soif. Le fermier lui apporta un mélange de café et de calvados et Drew resta sur place. Vers 22 heures, le fermier revint et dit à Drew de le suivre, mais de ne pas marcher avec lui. Ils se rendirent dans la maison en pierre au sol en terre battue du fermier où Drew s'assit dans la cuisine avec le fermier, sa femme, son fils et sa fille et son ami Ernest. Ils mangèrent de la soupe, du pain noir et du vin. Drew dormit dans la grange pendant environ une semaine, se cachant dans les champs pendant la journée. Après 4 ou 5 jours, la résistance française le prit en charge. Il fut confié à Georges Castelaine à Pont-l'Evêque qui l'abrita dans son auberge/restaurant. Il resta avec la famille de trois personnes pendant quelques jours. Il y avait un officier de marine allemand de haut rang dans la pièce d'à côté. Le Parisien Pierre Cornet est venu en tandem un dimanche après-midi et l'a emmené à 24 km de là, à la ferme Edouard et Clara Lanos, Ouilly-du-Houley, où il est resté 5 semaines (en juillet/août). Un certain André s'y cachait aussi et c'est lui qui apportait à manger. Drew et André jouaient aux dames pour passer le temps. Le E&E288 de Lionel Drew n'est pas disponible à la NARA (une page vide…) et le reste de l'histoire et les détails qui suivent proviennent des archives des French Helpers. Pierre et Francine Cornet sont venus chercher Drew et l'ont emmené à Paris via Lisieux, une ville à 10 km au sud-ouest d'Ouilly-du-Houley. Trois jours plus tard, Pierre Cornet a emmené Drew de Paris à Joigny (Yonne) où il a été confié à Pierre Argoud d'Aillant-sur-Tholon. Anthony-Marie Leriche de Joigny avait également aidé Drew sur son chemin. Récit de la fuite du Lt Drew: - (Pierre Argoud and his wife sheltered Drew and three other evaders RAF airmen (F/O D.F. McGourlick and his crewmen, Sergents H.L. Nielsen and T.H. Adams) for a few days until 18 August 1943 when Drew and McGourlick were taken to stay with Mme Maxine Carre at Saint-Aubin-Château-Neuf, while Nielsen and Adams were sheltered with Lucien Boudot at Bleury. Mme Carre sheltered Drew and McGourlick from 18 August 1943 until 6 September when they and Nielsen and Adams were taken to Paris by Jean-Claude Camors and Pierre Charnier. Camors sheltered Drew and the others for two days in his apartment before they were moved to the Grand Hotel de France in Paris. Drew and the others left Paris on 21 September for Nantes and remained in the area until 5 October when they left for Vannes (Morbihan). [ On 11 October 1943, Camors was shot by the French traitor and German infiltration agent Roger Leneveu at the Café de l'Epoque in Rennes and died of his wounds that evening. ] Drew, Adams and Nielsen left the Nantes area on 7 October. They were taken to Saint-Nic (Finistère). Mme Vve Chistine Magne, of Brest, had sheltered Drew, Nielsen and Adams at her home in Saint-Nic until 21 October 1943 when they heard the Gestapo were hunting for Mme Magne's sister, Ghislaine Niox. Ghislaine and Paul Le Baron took the three evaders to Brest where they stayed overnight with Mme Magne's parents, Colonel and Mme Scheidhauer at 1 rue Neptune. The Scheidhauers passed Nielsen, Adams and Drew to Daniel Phelippes de La Marnierre and his wife Yvonne at rue de Traverse in Brest on 22 October 1943. After almost two weeks, they were guided to Landerneau. On 3 November, Drew, Adams and Nielsen and other evaders were led to the Guennoc Island where they were supposed to contact a British boat party. They waited there for five days without any form of shelter and with food for only one day. The group was recovered and brought back to the mainland and spent the night at Mme de La Marnierre’s château at nearby Lannilis, the group being split on the following day. Drew, Adams and Nielsen were led to 17 rue Voltaire in Brest, which also belonged to Mme de La Marnierre. Due to bad weather and other problems, it was only on 26 December 1943 that Drew and 10 other American airmen, the 2 RAF men Adams and Nielsen, as well as 6 Royal Navy personnel boarded a British Motor Gun Boat (MGB 318) at Ile-Tariec (Brittany) in Operation FELICITATE. Drew was back in England the following day. Original) - (PARTIE II - Source: www.americanairmuseum.com via S Lanham) - Traduction DC via Google): Pierre Argoud et sa femme hébergent Drew et trois autres aviateurs de la RAF en fuite (le F/O D F McGourlick et son équipage, les Sgts H.L. Nielsen et T.H. Adams) pendant quelques jours jusqu'au 18 août 1943, date à laquelle Drew et McGourlick sont hébergés chez Mme Maxime Carré, Saint-Aubin-Château-Neuf, tandis que Nielsen et Adams sont hébergés chez Lucien Boudot à Bleury. Mme Carre héberge Drew et McGourlick du 18 août 1943 au 6 septembre, date à laquelle ils sont emmenés à Paris avec Nielsen et Adams par Jean-Claude Camors et Pierre Charnier. Camors héberge Drew et les autres pendant deux jours dans son appartement avant qu'ils ne soient transférés au Grand Hôtel de France à Paris. Drew et les autres quittent Paris le 21 septembre pour Nantes et restent dans la région jusqu'au 5 octobre, date à laquelle ils partent pour Vannes (Morbihan). (Le 11 octobre 1943, Camors est abattu par le traître français et agent d'infiltration allemand Roger Leneveu au Café de l'Epoque à Rennes et décède de ses blessures le soir même.) Drew, Adams et Nielsen quittent la région nantaise le 7 octobre. Ils sont emmenés à Saint-Nic (Finistère). Mme Vve Christine Magne, de Brest, a hébergé Drew, Nielsen et Adams chez elle à Saint-Nic jusqu'au 21 octobre 1943, date à laquelle ils apprennent que la Gestapo recherche la sœur de Mme Magne, Ghislaine Niox. Ghislaine et Paul Le Baron emmènent les trois évadés à Brest où ils passent la nuit chez les parents de Mme Magne, le colonel Scheidhauer et Jeanne [morte en déportation] au 1 rue Neptune. Les Scheidhauer confièrent Nielsen, Adams et Drew au Comte Daniel Phelippes de La Marnière et à son épouse Yvonne, rue de Traverse à Brest, le 22 octobre 1943. Après presque deux semaines, ils furent guidés vers Landerneau. Le 3 novembre, Drew, Adams et Nielsen ainsi que d’autres évadés furent conduits à l’île Guenioc où ils devaient prendre contact avec un groupe de bateaux britanniques. Ils y attendirent cinq jours sans aucun abri et avec de la nourriture pendant un seul jour. Le groupe fut récupéré et ramené sur le continent et passa la nuit au château de Mme de La Marnière à Lannilis, à proximité, le groupe étant séparé le lendemain. Drew, Adams et Nielsen furent conduits au 17 rue Voltaire à Brest, qui appartenait également à Mme de La Marnière. En raison du mauvais temps et d’autres problèmes, ce n’est que le 26 décembre 1943 que Drew et 10 autres aviateurs américains, les 2 hommes de la RAF Adams et Nielsen, ainsi que 6 membres de la Royal Navy embarquèrent à bord d’un bateau canonnier britannique (MGB 318) à l’île-Tariec (Bretagne) dans le cadre de l’opération Felicitate. Drew était de retour en Angleterre le lendemain. |